John Pordage and Divine Wisdom

Thoughts on one of the most Significant Works of Sophiology

Like a normal person, I spent the first week of my daughter’s life reading John Pordage. I didn’t really plan it. Around day two or so, I simply picked up his book Sophia, took it outside, and started reading it. And man—it is a resonant book! Sophia, which is probably one of the most important books in the history of Sophiology; this is a book I simply couldn’t put down. I immensely enjoyed it.

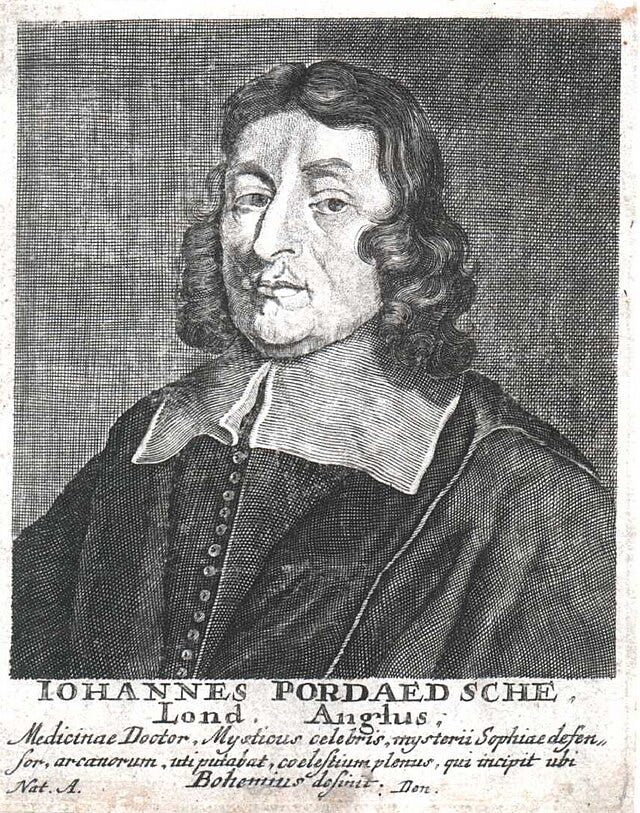

Part of what I enjoyed about it was that John Pordage writes a lot more clearly than Boehme. Pordage was an Anglican Priest in the 17th century who was deeply influenced by John Sparrow’s translations of Boehme from the German. He encountered Boehme as basically his spiritual mentor: while reading him, he experimented with different modes of piety, gathering his own sort of pietist conventicle of English mystics around him. Boehmist theosophy was confirmed to him by visions, which are recorded in the Sophia text I read this last week. Sophia Herself came to John Pordage, to teach him about regeneration, or the mystery of rebirth. Within this mystery, she taught him, lies the true art of arts, the sacred chemystry, the divine philosophy—with it comes a knowledge of the cosmos and the self, as well as path towards divinization. What was this path? Pordage describes it as four gates, each with a golden key.

The Pedagogy of Divine Wisdom

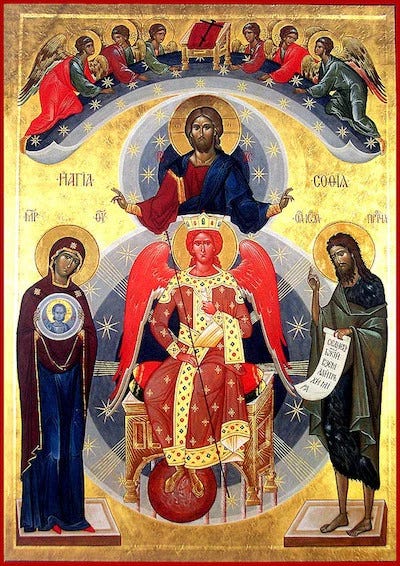

Sophia is first and foremost a book about Divine Wisdom. The revelations that Divine Wisdom gives to Pordage bring Pordage into a practical and intimate life of spiritual exercises, preparations for experiencing union with God. Wisdom is in a sense God’s agent of new creation, or God’s forerunner: she comes to set everything aright, so that the creature can enter into the eternal abode of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Wisdom enacts her pedagogy through evocation. That is, by her first revelation, she strikes in Pordage such a hunger and thirst that he cannot be satisfied with earthly things. And then she shows him her beauty—the splendor of Wisdom, how she makes all things green and verdant, how, when the heavens and the earth are in unity and harmony, all things become luscious and fruitful. She shows him the high dignity of the eternal spirit, the man who was created to enjoy this marvelous original creation. She shows him her Wisdom-fires, by which she fashions and refashions all things. And she shows him her abyss, where all things exist within her chaos, in potential but not actual form.

Wisdom also shows Pordage the nature of the human spirit. She tells him that there is a difference between the spirit and soul in man, though both of these are man’s “heaven” along with the senses. She shows Pordage his earth, in which he partakes of the four elements, his heart and passions. She shows him that in his spirit God wishes to dwell, like in a Temple—in fact, God wishes to dwell in man’s heaven and earth entirely, like he did at the first creation. And she tells him that she, Wisdom, knows the secret of the philosopher’s stone, which can transmute mankind’s earth into gold, into the elixir of life, into the fifth element, which is transparent unto the spirit.

The First Gate

So Divine Wisdom for Pordage is a rhetorical figure. But this means that she gives Pordage this wonderful vision of the beauty and harmony things to elicit a reaction within him. He is not to simply sit and marvel at the intricacies of divine wisdom, nor to take a taxonomy of all that is. Rather, Wisdom is ushering him into self-knowledge. And this self-knowledge is not only a knowledge of his own dignity, but also a knowledge of his state of fallenness.

Throughout Sophia, Wisdom attempts to convince Pordage that he is still in need of her guidance and pedagogy. And Pordage is at times resistant to this. He says things like “haven’t I been following you for x amount of years” and “I thought I already had undergone the rebirth on such and such a date.” Wisdom is patient with him at first. She says that for all of Pordage’s life, she has called to him, beckoning him onto the path of rebirth. But when Pordage makes this complaint a second time, Wisdom is harsher. She tells him that it is indeed true that Pordage at one time sought Wisdom earnestly. But like most men, he soon slackened, and backslid into his old ways. Now, Wisdom herself has come down to call him more forcefully, as a mercy for his weak condition. She was not content to see him be like other men; but instead, wanted to bring him into sainthood, into the highest degree of glory.

As Wisdom brings Pordage self-knowledge, she takes him through the first gate. There are four gates that Wisdom teaches Pordage he must enter into, in Wisdom’s pedagogy. The first gate is called the Gate of Conviction. Pordage has seen the beauty of the original creation; he has seen how the outer Genesis account of creation really describes his inner state, that he was created with an inner earth and an inner heaven, in which God was meant to reside like in the Temple or in the Paradisal Eden. He learns that he was meant to be verdant, life-giving, and ordered.

Man and cosmos exist in a certain ecology, Wisdom teaches Pordage. That is, just as there is an external world made up of heavens and earth, so is there, in Pordage, an internal world made up of heavens and earth. The heavens, on the one hand, are threefold, made up of spirit, soul, and body. The spirit is the intellect; the soul is the will; and the spiritual body is the senses. The earth is the heart, which is made up of the passions. Just as heaven is of a more subtle and fine quality than the earth, so is the mind of a more subtle and fine quality than the heart and must rule over it. Wisdom teaches Pordage that the natural state of man is one that is ordered, both within himself and within his wider world. Of course, this is wisdom’s business, for the biblical wisdom literature identifies Wisdom with the principle by which all things were created and all things are therefore restored.

For all things, Wisdom teaches, though they were initially permeated by wisdom, have fallen into abject disorder, both original and actual sin. That is, the entire creation has become corrupt, both the external creation and the internal creation. This is the thrust of the self-knowledge that Wisdom teaches Pordage, that he must confess that not only his passions, his heart, his earth, but also his heavens, his intellect, will, and senses, are fallen and corrupt. His heaven and his earth are out of sync with one another. His heavens do not rightly rule his earth; his earth is not verdant and teaming with life. Rather, he is barren inside, everything is out of joint, and he is not filled with wisdom’s love-fires, which is real concern for other people. Wisdom tells Pordage that this is the beginning of his path toward beatitude and divinization: to recognize the direness of his situation, to accept that his old earth and old heaven both need to die.

The Second Gate

This revelation leads Pordage to Wisdom’s Second Gate. The Second Gate is the Gate of Destruction, where Wisdom consumes the old heaven and earth by fire. Wisdom leads Pordage to the Scriptures, where he encounters all of the apocalytic imagery about the destruction of the old heavens and the old earth, and she transposes this imagery to be about his heart and intellect. That is, in order for something new to arise, Pordage’s heart and mind, all his selfness and sin, must be destroyed.

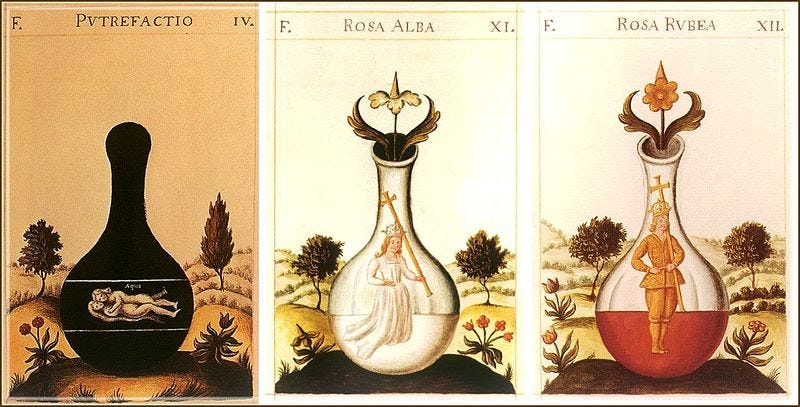

But what does this mean, that the old earth and heavens need to be destroyed, consumed by Wisdom’s fire? Pordage is adamant that this does not mean that the eternal essences of his heaven and earth must be burnt up. Wisdom is not teaching about a replacement, but rather a regeneration: it is the qualities of inner earth and heaven, the weeds of selfness and pride, that must be uprooted, blazed away, by wisdom’s love fire. The old earth must be smelted, refined—it must go through the alchemical process of dissolution or putrefaction, when the alchemical mixture returns to the state of undifferentiated primordial matter, if it is to be fashioned into gold by its exposure to the divine tincture, the philosopher’s stone. Pordage discusses this process before describing the gates, on pages 102-104, where he describes the philosopher’s stone, the threefold furnace, and the instigator and instructor of this “great work” (a common term for alchemy). It might be worth looking at Pordage’s explanation at length.

Pordage says,

In this earth of his is present the material essentiality of the stone of wisdom, the elixir and the transformative stone, which is called the son of the wise or the philosopher’s stone. O you devotees of Wisdom! This precious stone of divine Wisdom is such a pure treasure hidden in the field of man’s own eternal earth within him, that is, in the inward ground of his heart. This treasure is more precious than rubies; its acquisition is more desirable than God; it is utterly incomparable. It brings riches and honor to the inward man; it confers abundance and beatitude; it liberates the inward man from all scarcity, hunger, and thirst; it drives away al trouble, sorrow and sighing. Blessed and happy is the inward man who discovers these mineral gold-seeds within himself.1

However, mankind does not have access to this stone without performing the great work. In the middle ages, alchemists often spoke about the great work, which was creating the philosopher’s stone. The philosopher’s stone was a tincture: when it was applied to other bodies, it could supposedly transmute them into gold. Though there was a great fervor in alchemical circles during this time period, alchemy was not often thought about as an esoteric or magical discipline; rather, it was simply thinking through the implications of the natural science of the day. If Aristotle was right, and all of the elements derive from a prima materia, then why wouldn’t one be able to, after reducing the materials back to this substance, be able to shape matter into other, more beautiful and expensive forms? Alchemists thought that this could be possible: but what was needed was a special tincture or agent of transmutation. It was thought that, if one could succeed in creating a special stone, the philosopher’s stone, this might be accomplished.

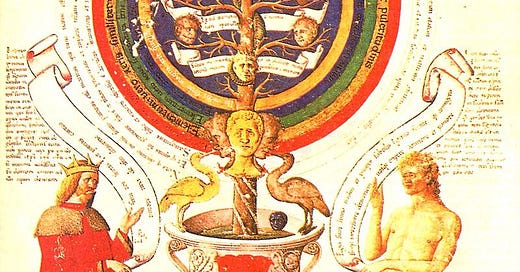

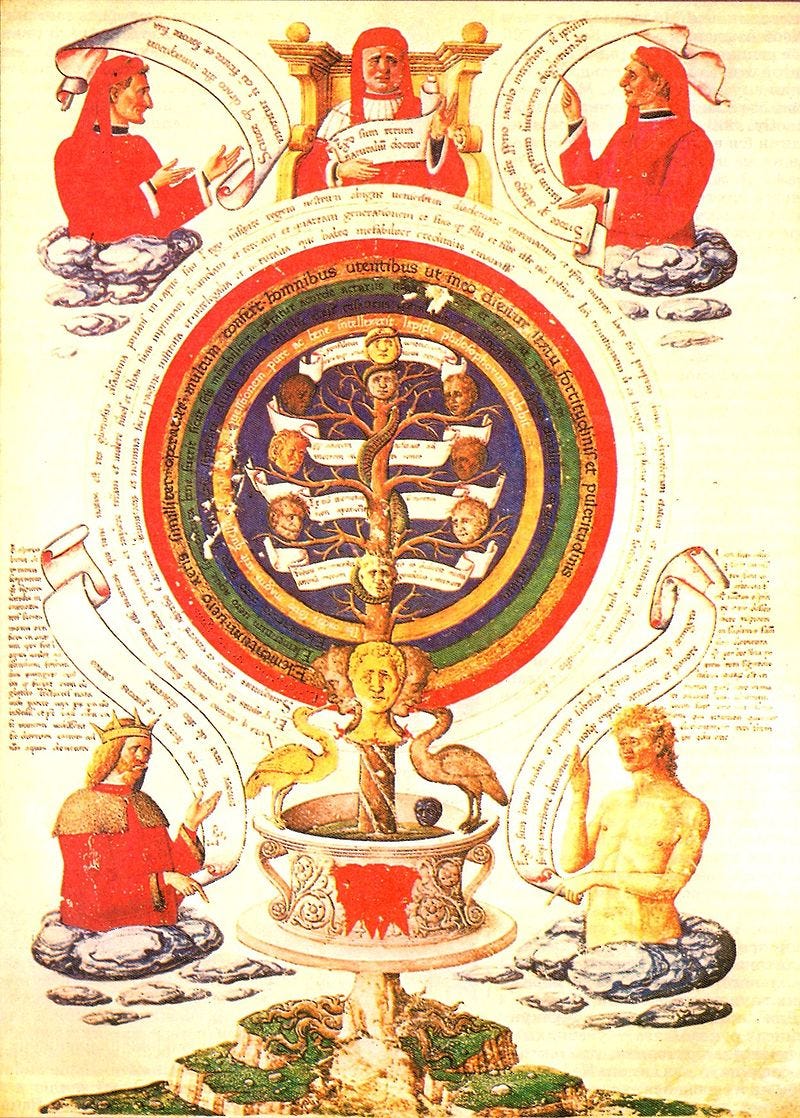

Alchemy of course became a more esoteric discipline during the renaissance. Part of this is due to the fragmentation and revision of medieval education, which prioritized allegorical/pictorial representations of the arts over theoretical explanations: medieval alchemy became more esoteric partly because cultural models of reading changed so drastically. Another reason this tradition became part of the esoteric traditions was due to the renaissance discovery of classical alchemical texts, which often linked alchemy with a theurgic or spiritual path. Hermeticist such as Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola popularized alchemy within their neoplatonic Christian theology; Heinrich Agrippa attempted to blend hermetic philosophy with alchemy and kabbalah in his De Occulta Philosophia; and Paracelsus, the “Second Luther,” founded a discourse in which alchemy, medicine, and theology all merged into a coherent whole.

Paracelsus was particularly influential on the German spiritualist tradition, especially Valentin Weigel and Jacob Boehme. There’s a really good book tracing this tradition, called Spiritual Alchemy: From Jacob Boehme to Mary Anne Atwood by Mike A. Zuber. Pordage stands within this tradition identified by Zuber, for he uses this loaded alchemical language to discuss the spiritual transformation of the individual. Alchemy for Pordage provides the structure of his revelation from Sophia: Sophia wants to smelt him down and remake him into a divine sort of thing, separating all that is sin and egotism within him from the original, divine image. She wants to refine him, but also to transmute him, making his heavens and earth into new heavens and a new earth, a renewed mind and renewed affections. His book is the spiritualist rebirth sung in an alchemical key, just as it is in Boehme. Wisdom is the agent by which the philosopher’s stone is crafted and the old man is tinctured into the new.

The Third Gate

The Gate of Destruction is followed by the Gate of Dissolution. In this gate, Pordage learns how to correspond the revelations of Wisdom with the secret sayings of the prophets and the Apostles. This is incredibly important and should not be overlooked: Wisdom leads Pordage back into the Scriptures, not away from the Scriptures and into some type of nebulous personal experience. At this Gate, Pordage realizes that it is a divine revelation that all of his selfhood must be rooted out, all of his egotism and sin, so that Wisdom might be able to bring about a new creation in him. He also finds out that the general thrust of the Scriptures attempts to convince Christians of the necessity of Wisdom’s work and the new birth, though sadly, many are blind to these promptings.

Wisdom presents a unified injunction towards rebirth from the Old Testament to the New Testament. Especially featured are the prophetic and apocalyptic literature in both testaments, especially the major prophets and St. John’s Revelation. Here we see a beautiful spiritual exegesis of Christian apocalypticism and eschatology. Pordage is nebulous about whether or not all of the things predicted in the Scriptures will happen to the visible heavens and the earth—but one thing he is sure of is that these things must happen in the invisible heavens and earth, the human heart and mind. These must be brought under the awful judgment of God, unmade by his mighty word, brought low by the ministry of John the Baptist, brought under the consuming fire of God’s Holy Wisdom. One might critique this as a retreat to the immanent frame, that Pordage is despising what is outward; but I don’t think this is a helpful way to designate this spiritual exegesis, for two reasons. One, Pordage stands in a long tradition of reading the Scriptures according to the medieval “moral sense” of the text. In that sense, his readings don’t stand out very much, even in a post-reformation protestant context. And secondly, Pordage reads the inward through descriptions of the outward. That is, there is still a link between the two, even if the direction moves inward. In this sense, he does not represent a secular “cutting off” of the immanent from the transcendent, the inward from the outward. Rather, he is attempting to get a sense for the inward by means of the outward (more on this later).

The Fourth Gate

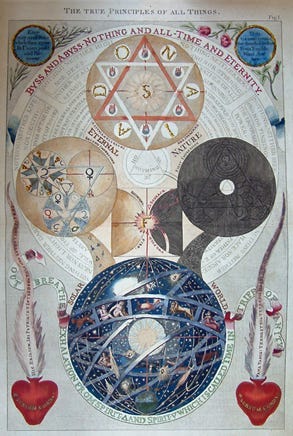

The final gate of Wisdom Pordage calls the Gate of New Creation, which is also the Second Gate of Renewal. Here Pordage describes what the end of Wisdom’s pedagogy leads to, what he calls the magical heavens and earth. That is, the entire alchemical process pushes towards an end, which is the refining of a transparent earth, a spiritualization of matter, the interpenetration of God and humanity. By breaking down and destroying our selfhood, Wisdom prepares us to be transmuted and smithed in her divine fires into something that is beautiful, something that reflects the divine glory: in fact, something that looks like Herself. She aims to awaken the internal eye, so that we can see the invisible earth and heaven all around us, so that we can gaze with wonder on the invisible foundations of reality. She wants to purify out minds and hearts, so that we can think and feel rightly, submitting our entire selves to God’s Will. She wants us to be united to her, as she is united to God.

This union with Divine Wisdom, which is really a union with the entire Trinity, brings about new attributes in us. Not only does it make our earth’s verdant and our cosmos’ ordered. It also brings about the fruit of the Spirit, which Pordage lists from time to time. It brings in us a sense of peace and love, by which we can become active participants in God’s energies, using our own energies to be his agents in the world around us. Sometimes, because of his emphasis on sinking into the ground of our being, Pordage is described as not believing in any form of regulated work or action. But I don’t think this is quite right. Sophia actually brings the Christian into an active receptivity from God, by which he is able to see things the way they are and act in the world according to this new reality.

For it is, indeed, a new reality that Sophia brings Pordage into. She teaches him the true nature of this world, the dark world, and the light world. She teaches him that there are innumerable worlds and habitations created after our world. She shows him that these worlds exist as destinations for the myriad of souls who are on their way to beatification, but are not yet pure enough to enter the abode of God. “In my father’s house there are many rooms”, as Jesus said. Pordage latches on to the Orthodox Protestant acceptance of degrees of glory (maintained, for example, in Lutheran confessional circles), arguing that even though everyone who is given the grace of the Father and the Son is indeed saved, there are different proximities or degrees of glorification in the heavenly realm. There are many different mansions, some reserved for the weak, others for the strong. All things are fitted for our progress into God, our deification: and after death, if one dies being merely a spiritual child, Wisdom will continue her work in you and bring you ultimately to the blessed purification and union with God. Purgatory, Pordage says, obviously does not exist—and yet, the impure cannot remain with the pure; ultimately, what is partial must come into completion, as is promised in the Holy Scriptures. It is difficult not to here think of Bulgakov’s extended meditations on the life of spirit-souls after death, or Gregory of Nyssa’s speculations on ghosts in De Anima.

Wisdom also teaches Pordage about the nature of these worlds. Initially, there was only Eternity, she says. Pordage divides these eternities into the “Quiet Eternity” and the High Eternity, which are also present with God’s Abyss, the depth of his gottheit. From these came the angelic sphere, which was at one time in complete harmony with God; but from the angelic sphere fell Lucifer and his angels, who through their rebellion fashioned themselves a dark home and a draconic principle. God was not responsible for their fall, Pordage maintains: rather, their fall was due to their selfness, their obstinacy and anger, their exiting of the angelic realm within God. God does not create hell for anyone, nor does he cast them into it; rather, they create it for themselves by asserting their self will against the divine will. This hell follows all self-willers all their life long.

Though he did not create the Realm of Darkness, God did create the World of Light as an outgrowth of the goodness of his being. This is the paradisal creation, which we see in Genesis 1 and 2. By Wisdom, God declares, “let their be light”: and this new world comes into being, full of his own radiance. Here God creates the Eternal Spirit, Adam, who contains within himself all of the human race. The visible world we see now is only an outgrowth of this eternal light world, which retracted due to Adam’s fall. Through the pedagogy of Wisdom, this now invisible light world becomes visible to our inward eye, and we see the world as it was originally created, as transparent unto the divine nature, as a place of cosmic beauty.

The relation between the visible and invisible worlds is very interesting. As I said above, originally the spiritual creation was the visible world; in this world God walked, in this world Adam worked. It was the outer world that was invisible at this point, overshadowed by the sheer glory, a mirror of the divine nature. But with Adam’s willful sin, Pordage tells us that this light world retracted; the outer world became the visible world, and the inner world became the invisible world (as we know it today). Both words are present in the same space; both worlds are in a sense “this world.” But there is a play between the visible and invisible here in Pordage’s revelation of sophianic wisdom. The foundations of the World are in some sense esoteric, hidden, waiting to be revealed in their spiritual concreteness. The same is true, Pordage is obviously arguing, with man, as well. Or, said another way, this revelation of the spiritual world is the revelation of the spiritual significance of mankind’s inner world.

Did God create other realms after his creation of this world? Pordage doesn’t see why not. We need to get away from the idea that there are only two worlds or two principles, heaven and hell. Rather, there are an infinite amount of realms, corresponding to the diversity of needs of the human being. This is what befits God’s majesty and goodness, not that he sends the pure to heaven and everyone else to hell. There are, of course, Pordage confesses, a vast majority of souls in hell. But this is because of their own shutting out of the light, their own anger and obstinance, their own residing in the principle of evil—not due to God’s condemnation or judgment.

When the principle of light retracted, this created an opportunity for the world of darkness to penetrate into this world. And this too plays a role in the question of hell for Pordage. The principle of darkness has entered this world and made it barren. The powers and energies of darkness ravage the earth and entice men and women to pursue evil. It lights a dark fire of desire within their hearts, so that they are overcome with a lusting after all things that are contrary to self-abnegation and obedience. It creates in them a longing for a perverse union with the power of the dark principle; and in the end, if they persist in it, God will allow them to be united with that principle in the hell of their own making. In some ways, this is a bit like what happens at the end of Narnia, when Tash and Aslan both take their own with them on the last day. It is also like the end of The Princess and Curdie, when the misshapen creatures go off with the unfaithful stewards, who are never seen again.

Thoughts and Reflections

There isn’t a whole lot of room to reflect on all that. But I do want to point out a couple of things that struck me while reading. I think when I come to texts in the Boehmist tradition, I often come with a list of presuppositions, things I think I know about the tradition. Some of them were proved right by this book, others were proved very wrong. Let’s talk them through a little bit, and see what can be seen.

First, Pordage is often put in the genealogy of spiritualism. And so, I expected this book to be pretty skeptical about the external and material world.

This first concern did come up occasionally. Even the way that Pordage configures his world shows a preference for the internal over the external. And there are a few moments throughout the text where he is deeply critical of the externals of Christian worship. Whenever he mentions it, he always refers to the sacraments as “bread” and “wine” and “water”—and I think this is to purposefully to point out the externality of the rights, that they are not concerned with the vital subject. And he talks about them in the same breath as denouncing vestments and other external matters of piety.

Pordage in this way, like a true spiritualist, distances himself from the ecclesial community. But I think it is worth pointing out, though, that Pordage received these revelations while he was in fact a priest, living the way of life that he was ordained into while simultaneously receiving revelations from Sophia. And whereas Sophia convicts him of being unconverted, she does so deftly, not by throwing out everything that is past; rather, she incorporates it into her divine pedagogy, on the one hand saying that she has been calling Pordage all along, and that he has for a long time been in the process of regeneration, and on the other hand saying that the reason for her descent is that Pordage has refused to fully remain in her center, and has instead embraced a life characterized partially by self-will. Just as the heavens and the earth must be regenerated and not destroyed, so Pordage’s way of life is at once confirmed and then sublimated into a higher pedagogy. Wisdom does not erase or do away with the work wrought in Pordage by the Father or the Son; instead, she comes as an aid to this work, to bring it to completion so that Pordage can enter into the highest degree of glory when he goes to heaven.

Furthermore, Pordage actually distances himself from separatist perfectionist groups, such as the Quakers. And I think this is important, as well. In his fourfold typology of separatist pietism, Douglas Shantz argues fairly convincingly that not all radicals were separatist. Groups like the Boehmists were content to continue to receive the sacrament and worship in the external church, all the while practicing inner renewal. I think it would be a mistake to read Pordage as simply another person who threw out the communio sanctorum; his Boehmism was actually in some sense a church piety, based as it was within the logic of the sacrament of the altar.

Andrew Weeks argues for this point concerning Boehmism extensively (and persuasively in my opinion). I worry, though, that this element of Boehmist theosophy is not explicit enough in Pordage’s Sophia. This would mean this spiritual text is missing an explicitly theurgical dimension which is at the heart of the Lutheran Reformation, but which is understood in theologians like Solovyov and Bulgakov (because of their personal experience within the Russian Church). Perhaps, though, the best rebuttal of saying that ecclesial community and family life are contrary to the way of life Wisdom has inculcated into Pordage and which he promotes is to point out that Pordage himself lived a very full family life and continued to be a priest even after he was forced out of the Church of England.

Second, Pordage is writing as a theosopher and not a philosopher or theologian, so I was expecting him to have deficient metaphysical language and concepts.

Bulgakov critiques Boehme for reducing all of reality to will and subjecting God to his own abyss. He also rejects the myopic nature mysticism in this tradition, arguing that it reduces reality to a single point, misunderstanding its natural three-ness. When I began reading Pordage, I expected him to make similar moves, maybe even locating evil within the dark will of God.

But interestingly enough, Pordage doesn’t really do any of this. In fact, he shows himself as fairly philosophically astute, using a complex, tripartite anthropology, correlating this anthropology with his cosmology, and providing a convincing schema of transcendence which endues everyday life with meaning. This philosophical acuteness comes out when he talks about the relationship between Sophia and the Holy Trinity, or the origin and nature of evil. All of a sudden, Pordage starts using Aristotle’s four causes, or the distinction between primary and secondary willing, features which are more common in scholastic protestant spaces than among mystical writers. It was refreshing to find this philosophical sensitivity in Pordage: some of the eccentricities of Boehme’s visions are here tamed, and one can see that Pordage is attempting to navigate his experience of Sophia within traditional categories, much like Sergius Bulgakov after him.

Third, I was interested to see what Pordage had to say about hell. His source material, of course, believed that hell had a foundation within God himself, in his anger-fire. His successor, on the other hand, was a universalist according to the patristic model of Apocatastasis.

Interestingly enough, I think Pordage represents a transition figure between Boehme and Leade. Whereas Boehme essentializes hell within the Father and the dark world, in Pordage we see a distancing of God from the principle of evil and from hell in general. Pordage is adamant, over and over again, that God is only love; a concept of a God who sends people to hell is unworthy of the name. But, Pordage is convinced, the Scriptures speak unanimously about hell’s existence, so it cannot be dismissed out of hand.

Hell finds its origin in the principle of the fallen angelic beings, who have refused God’s love-fires and entered into their own principle, and kindled the dark fire of resentment and evil. God did not create this place for the fallen angels, as we saw above; rather, they created it for themselves, as a place apart from God. And this hell is open to all of us, insofar as we are deceived by these demons and choose our self-will, instead of Gods. This strong evacuation of the deity from any anger or judgment will be characteristic of the Philadelphian circle after Pordage; only, Jane Leade will capitalize on these ontological and theological insights, arguing that they actually lead not to a doctrine of eternal conscious torment, but rather to a doctrine of universal salvation, patristic apocatastasis. As Nils Thune pointed out almost eighty years ago, one can already see the transitions in Boehme’s thought begin in Pordage—and I would argue that you can also already guess where those transitions will lead, with the prophecies of Jane Leade. It is deeply important to Pordage that we know that Sophia has not come to bring wrath on us. Rather, she has come to burn us up in just the right way—hot enough to burn up all the self-will, but not hot enough to burn up the essential being in which the qualities are planted. Sophia knows how to work the philosopher’s oven: she knows how to get things just right for transformation and transmutation, without over or undercooking Christians.

Divine Wisdom

Let’s speak for a little bit about Pordage’s Wisdom before I close. Nils Thune has criticized Pordage for being more of an intellectual and less of a prophet or visionary. But I think that, even though his visions are less prophetic—i.e. ecstatic—than Jane Leade’s, they still retain the capacity to deeply move the reader. Interestingly enough, Wisdom, for Pordage, constantly refers him back to the Scriptural testimony. And whereas for sociologists interested in the novelty of mystical experiences this can seem like inauthenticity, but for a Christian interested in mystical experiences, this is actually a really important indication of his visions’ authenticity. For really, if Wisdom is divine, wouldn’t it affirm the divine dispensation that had been handed over to the church in the words of the Apostles and Prophets? And if Wisdom has begun her preparatory work to inaugurate the Philadelphian age (which we know, of course, did not occur after the visions of John Pordage), would one not expect Wisdom to affirm the previous dispensations of the Father and the Son?

Interestingly enough, this is exactly what Wisdom said to John Pordage. That is, Divine Wisdom claimed to be the one who prepares the way of the Lord, like John the Baptist. Wisdom claimed to prepare the people of God for the return of the Son in the spirit and the regeneration of all things. In this sense, her ministry was after that of the Father (the Old Testament) and the Son (the New Testament)—but before the second coming and the Pentecost at the end of the age. Though we may find this way of phrasing things unfamiliar (or too familiar, if we live in areas that are deeply dispensationalist), it is worth noting that Pordage sees Wisdom not as usurping the role of Jesus or starting some other religion other than Christianity. Rather, Wisdom is a helper to bring Christianity to its fulfillment. Wisdom comes to enter the hearts and minds of unbelieving and erring Christians to bring them back into the Kingdom of God, to regenerate their hearts and minds to truly follow Jesus, to avoid sin, and to await the coming Kingdom. Most important here is the submission of one’s mind, will, senses, and appetites to Wisdom’s pedagogy, her alchemical process. Pordage stresses this again and again; in the tradition of Boehme, Luther, and Tauler, he counsels a spiritual posture of receptivity before the Divine, so that one can be vivified by the divine energies.

I chose that word carefully at the end there, the divine energies. For when one wants to know exactly what Wisdom is, Pordage is adamant that Wisdom is not a fourth member of the Holy Trinity. Rather, she is the energy by which the Trinity brings about its purpose. Wisdom speaks about herself to Pordage as follows:

No one is commissioned to do this work but I, I who am the virginal Wisdom of my Father, the Father who creates nothing without me. I, too, can do nothing without the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. Those men who confuse me, Wisdom, with the Father, and with the Son, or with the Holy Spirit, are foolish philosophers, for I am a spirit and energy that is differentiated from the Holy Trinity, but am yet one with the Holy Trinity. What I do, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit also do. I perform nothing from myself, but the Holy Trinity works in me. In this fiery day of mine, however, and in this my day of purification and refinement, the Holy Trinity accords me precedence for the sake of differentiation, so that Wisdom might be recognized, honored, admired and praised by her Children.2

Wisdom, for Pordage, is the spirit and energy of the Holy Trinity. She does not do anything without the Trinity; rather, she does what the Trinity does, only acting out of the divine will. She is the Trinity’s reflection, its mirror, its spiritual substance or body. She is its instrumental cause, by which it accomplishes its works. She was present, Pordage claims, at the Creation, when God made all things in Wisdom; she was present in Christ’s ministry, as the Forerunner, John the Baptist; and she will be present at the ripening of the cosmos, both that which is internal and that which is external, when all things come to fruitfulness and all things come under the great judgment and the cosmic refining fire of her Heavenly love.

I’ll leave off here. I hope you’ve enjoyed this little meditation on John Pordage!

Pordage, 102

Pordage, 191. See also 274-278